Borovnica railway viaduct 1850 – 1944

Borovnica

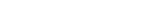

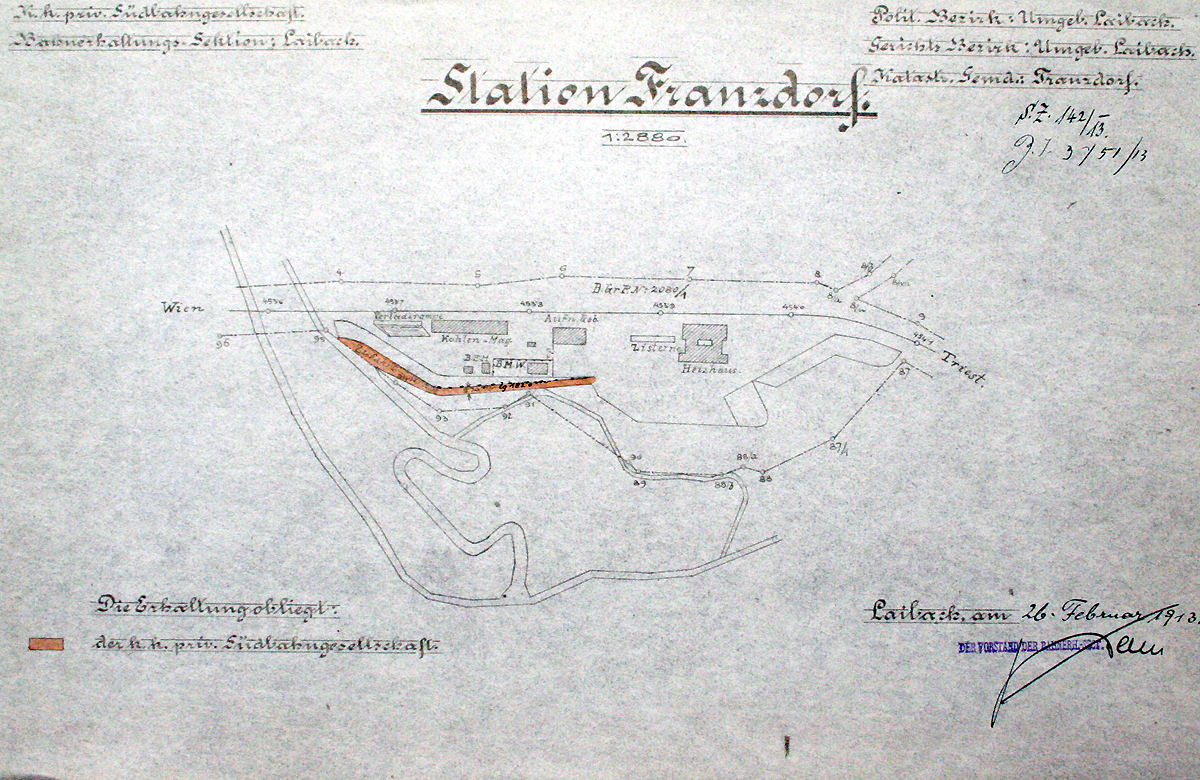

At that time, Borovnica, a small village in the southern part of the Ljubljana Moors, had about fifty houses. It can be only guessed today about the people of Borovnica feelings when they received a crowd of workers building the Viaduct. The fact is, however, that since that distant year of 1850, life in the village has changed radically.

Most of the workers coming to Borovnica were Friulians. They were accommodated in sheds around the construction site, especially in Laze and Dol. In order to provide supply for them, a kitchen was built in Dol, a medical station in Laze, and a market place on the meadow between Dol and Laze. Local names from that time have been preserved, e.g. kužnica (infectious house) and tržnica (market place). On Sundays, a mass in Italian language was held for foreign workers. Foremen and engineers mostly stayed with locals. Supply of a large number of workers was certainly a demanding task, and the entire village was involved in it. After the cholera outbreak in 1855, which significantly reduced the number of workers, a water supply system was brought from Zakotek to the construction site.

The railway construction was a good source of income for the locals. Some of them sold their land for construction purposes, others participated in the construction in one way or another, as construction workers and carriers. Jobs were also available in quarries and brickyards. Many farms were neglected during that time, as the desire for income temporarily diverted mainly men to the construction site. To supply labour force, locals were able to sell all their market surpluses during the construction, and trade and catering flourished. The arrival of the railway also triggered the development of the town. Roads were improved, and the construction of a water supply network began. Borovnica and its surrounding villages belong to clustered villages developed in the countryside in central Slovenia. Such a structure is characterised by houses somehow making a group, without a prescribed order. There is usually a main road in the village, with other roads connected to it. In Borovnica, it is today’s Zalarjeva cesta, along which houses and farm buildings crowded under the slope of Trebelnik, while gardens, orchards, fields, and meadows followed towards the Borovniščica stream. The old part of Borovnica and the surrounding villages have partially preserved this form until today.

Many things changed in the small town with the arrival of railway. Suddenly, the world became unusually close, and Borovnica and its surroundings began to develop rapidly. In line with provincial laws, the parish of Borovnica was established in 1869, covering the settlements of Borovnica, Zabočevo, Preserje, Kamnik, and Rakitna, with a total of 4,141 inhabitants. Borovnica alone had a population of 624 that year, and as many as 749 in 1880, and was ranked seventh in terms of the population growth among villages in Carniola.

Borovnica has always been known for its hospitality and strong national consciousness. A Reading Society was founded in 1874 and became a driving force of cultural and social life. On important anniversaries and other national holidays, people from near and far liked to come to the small village under the mighty Viaduct. Janez Borštnik, president of the Society, put a significant stamp to the movement.

A new school building was opened in Borovnica two years later (1876). Until then, young people were not mandatorily involved in education, lessons were given by priests or organists as part of religious instructions. It was pastor Janez Skubic who in 1848 initiated the establishment of a school. Lessons took place in the sexton’s house (today’s library). Fran Papler was appointed a teacher, and with his knowledge and actions, he significantly influenced national awareness, educational and cultural life in the town, and he was also actively involved in fruit growing.

In addition to social development, the railway also triggered rapid economic progress. The place changed its image. Large borough houses were built, shops and inns appeared, and a water supply network began to develop. The woodworking industry developed and became a driving force of the economy. Furniture factories emerged in addition to large sawmills. The most important were Kobi’s, Majaron’s, Petrič’s and Švigelj’s sawmills. The Southern Railway construction additionally accelerated already well-developed sawmilling in Borovnica as well as the exploitation of forests and the sales of wood to Trieste and elsewhere. The population structure was also slowly changing. Borovnica inhabitants got jobs in the railway and sawmills, some commuted to work elsewhere. The number of craftsmen increased. In 1868, the Great Assembly of the Agricultural Company proposed to establish a company branch also for Borovnica.

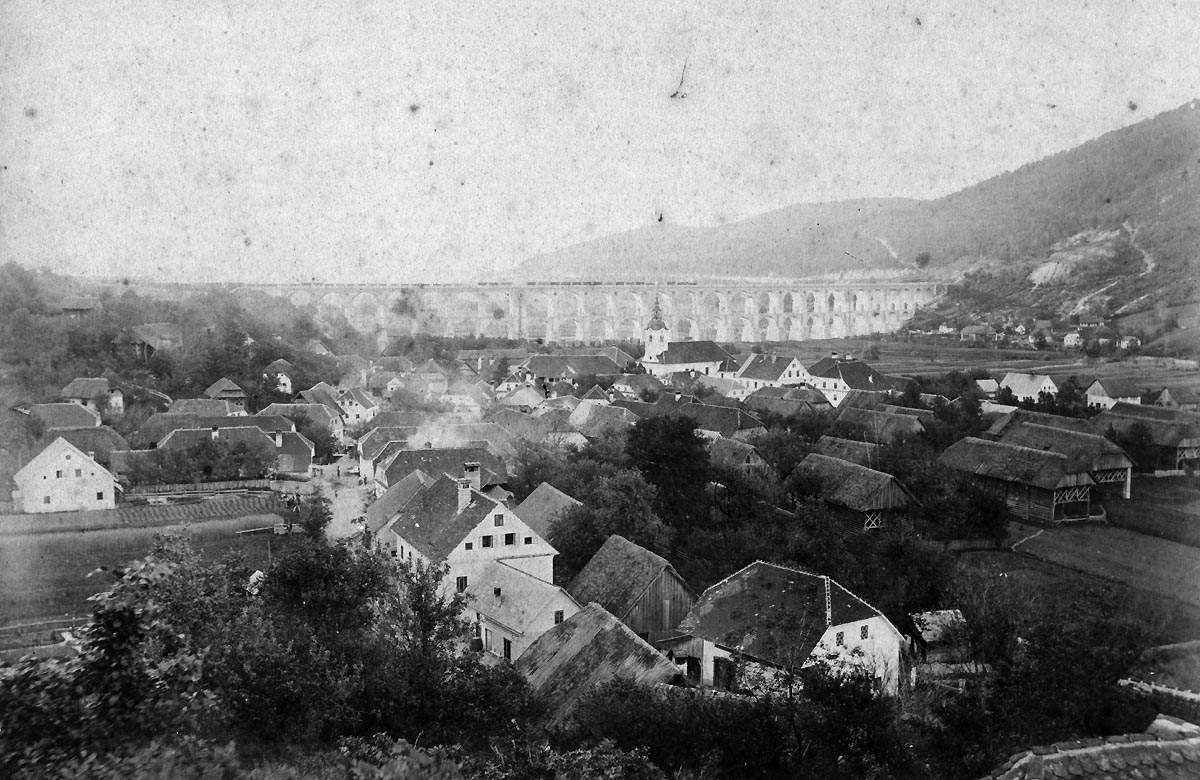

In spite of rapid development, however, a record had crept in the column of Potopisne črtice (Travel Journal Novelettes) published by Kmetijske in rokodelske novice, in their 49th issue, December 1894, which later proved to be very true: “Potopisne črte. From Ljubljana to Ljubljana / Authors: Jos. Levičnik. The next station, Borovnica, is famous for its giant bridge, which runs the railway very high above the valley with the same name right in front of the village. There are actually two bridges on top of each other at a height of about 20 fathoms. I described all of these: the bridge and the station, and the construction of the railway over the Ljubljana Moors, in the Society of St. Mohor’s 1874 calendar, pages 191 to 196, in a very accurate and thorough manner; therefore, I find reiteration of all these unnecessary here. Nevertheless, I am still mentioning one more today. Though many a man may shake their heads in scepticism when reading my thoughts, but I say them anyway, namely: our descendants may still experience the railway over the swamps and the Borovnica Viaduct being – a giant monumental ruin. Many of us seniors still remember how many doubts were raised about the construction of the railway across the Ljubljana Moors, and there was a lot of talk about the fact that its realisation should have been mostly attributed to the stubborn will of the then Minister of Trade, Bruck.”

In order for inhabitants to live in peace and security, an intention was found in the newspaper of 1880 to establish a gendarmerie station in Borovnica. In general, the 1980s were extremely interesting. In addition to the establishment of “Požarna bramba” (fire brigade), inhabitants of Borovnica were able to admire the new organ in the parish church and, as usual, they had a severe quarrel at the mayoral elections in 1881. However, there were also social events and festivities. The most famous moment occurred on Sunday, 15 July 1883, when the Emperor travelled through the village by train. In 1888, Borovnica even more strengthened its connections to the world. At the request of the municipality, High Imperial-Royal Ministry of Commerce allowed by order of 3 May the establishment of a post office-merged telegraph station. Its door was opened already on 7 August of the same year. Borovnica, however, avoided neither natural disasters nor diseases. In 1894, scarlet fever spread in the municipality. A lot of kids got sick, therefore, even the school had to close. The earthquake that struck Ljubljana in 1895 damaged many houses in Borovnica and its neighbourhood, especially the parish church of St. Margaret, and the parish.

Borovnica increasingly progressed also in the economic field. In addition to the woodworking industry, which was the main driver of the economy, the Mining Company received a licence to exploit iron ore on Kopitov grič in 1901. The Livestock Cooperative was founded in 1909 with the aim of promoting livestock farming. In June 1904, the Slovenian Mountaineering Association solemnly announced the opening of regulated trails in Pekel Gorge. Consequently, the Gorge became a popular excursion spot visited from near and far. Following the growing number of children, the school became a five-grade school in 1910, and the school building was running too small. Therefore, in June 1913, the local School Council issued a tender for the school building expansion by four classes. The construction of the extension was significantly delayed due to the First World War. It was only completed in 1925, and the school became a six-grade school.

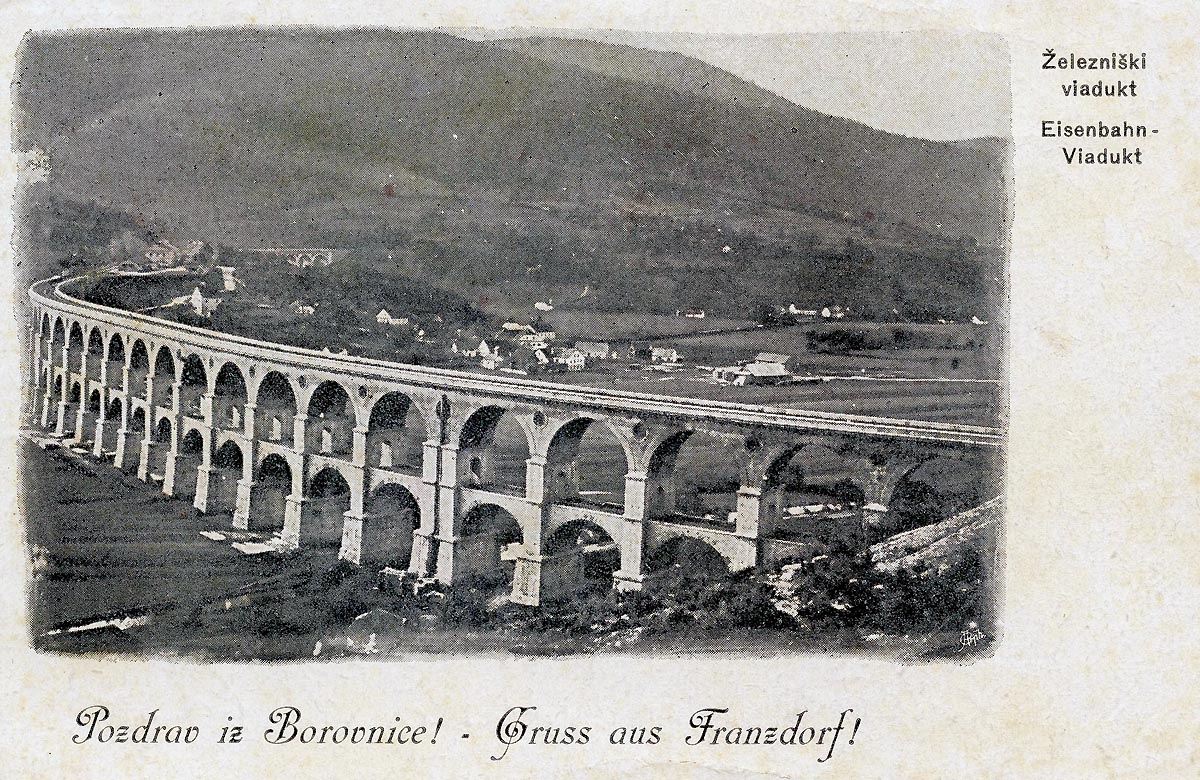

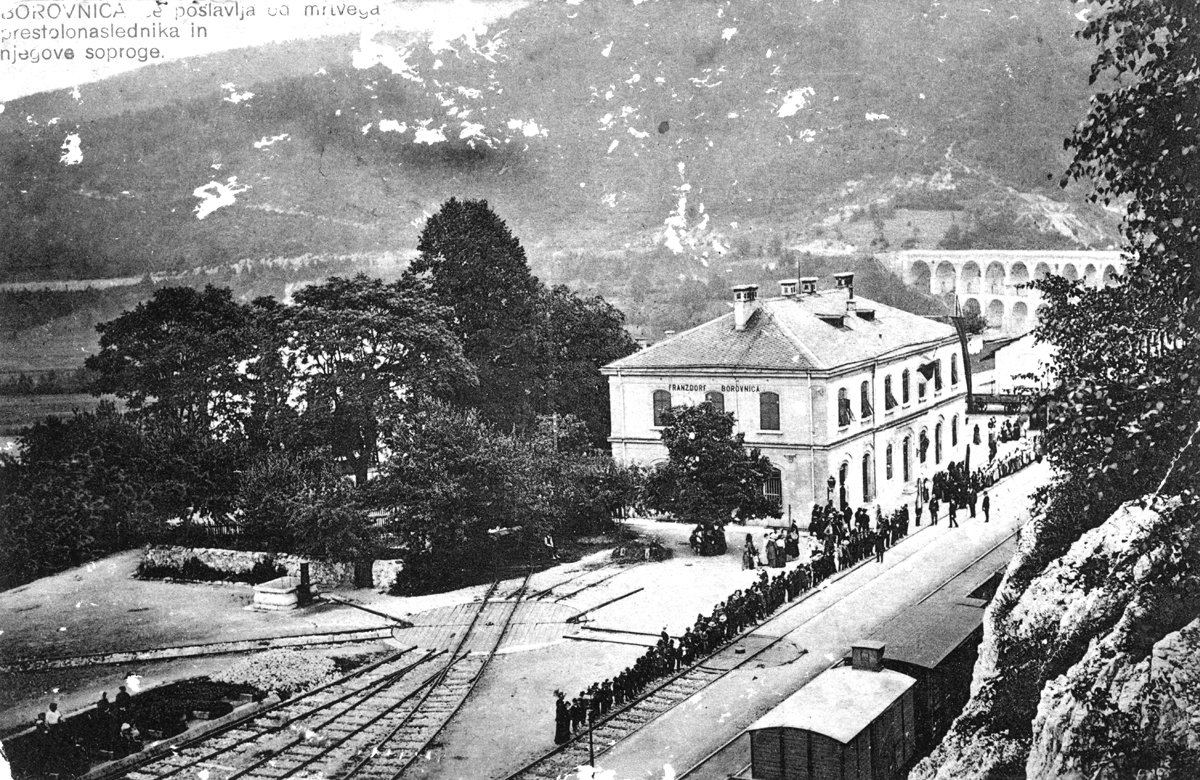

The Borovnica Station

On the plateau between the viaducts of Borovnica and Jelenova dolina, builders of the Ljubljana–Trieste line built a railway station. The buildings were built by Kotnik enterprise. The station was managed by a stationmaster. The station was completed by auxiliary facilities: a water supply station, warehouses, an engine shed, and a locomotive turntable. A chain of railway guardhouses was set up along the entire line; they aimed at signalling arrival of trains and inspecting the line. A nicely restored railway guardhouse No. 666 is located on the opposite side of the former Viaduct. It is the only preserved and restored original railway guardhouse on the entire Southern Railway route, and it is worth visiting. It is accessible by a marked path leading from the current railway station. On the left side, in front of the Jelenova dolina Viaduct, a side track with the channel for locomotive cleaning and water supply were set up, and their remains are still visible; however, they are not accessible due to the busy railway line.

As the line began rising steeply from the Borovnica Station towards Postojna, another locomotive was added as help to the back end of trains, pushing heavy wagons towards Logatec. The back locomotive returned from there to Borovnica, and the remaining train composition continued its way to Trieste.

The Station of Borovnica, which was called Franzdorf during the era of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, had great social significance in addition to the economic one. Borovnica people received on the Station their guests that used a train in large numbers to attend many events in Borovnica. Near the Station was a large and well-attended inn, its house is today used as a multi-apartment residential building. In 1914, the locals had said farewell at the Station to the Austro-Hungarian Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia, who were later shot by the assassin Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo. After the First World War and until 1921, the Station hosted the customs (due to the proximity of the border with the Kingdom of Italy, which ran between Rakek and Logatec at that time).

During the bomb attacks in 1944, the Station was badly damaged. When constructing the new line, the Station, for its unsuitable location and difficult accessibility, was replaced with a new one at another location; the engine shed was pulled down, while the building itself was repaired and turned into an apartment building. Even nowadays, this part of Borovnica is called

the Old Station.

Railway Guardhouse No. 666

Railway guard house belong to typical and most widespread railway buildings of their times. Guards used to live and work in them, and their basic task was to ensure safe traffic. In the time without telephones, telegraphs, and technically undeveloped signalling, traffic could only be relatively safe with the help of guards. Their tasks include constant monitoring the line in both directions and handling signals, raising and lowering railway gates at passenger crossings, observing passing trains and all railway installations, and taking appropriate action in case of irregularities. Guards also transmitted messages, and thereby quite successfully replaced the later telegraph. With a purpose of successful guard service implementation, guardhouses had to be placed very densely, even at less than 500 m, provided that they could be seen from one to another. They differ in size and shape. Their size was probably determined by the type and amount of work for a particular job, and their architecture was tailored to local requirements.

In the area of Borovnica, there are three types of guardhouses of different sizes. A smallest guardhouse with one room, middle with three connected rooms, and a large one with four rooms. The large guardhouse in Borovnica was preserved for a long time; however, with a new owner, it changed its appearance considerably. All of guardhouses are characteristic by an observatory, a kind of small, track-facing room with three windows, which allowed the guard to observe all sides. At the very beginning, guardhouses were mostly dwellings for guards and their families, and a workplace. Later, with the development of signalling, security and telecommunication devices, guardhouses lost their function and were only used as dwellings. Where the job was still needed, a wooden service hut was set up next to the guardhouse. Guardhouses were built in standard forms and technique along the entire line from Vienna to Trieste. This was also the direction of their numbering order.

Guardhouse No. 666 was upgraded and put into service in 1857. It is located at the old track, and it is the last one before the Viaduct. It is the standard smallest guardhouse leaning against the hillside. It is special for being located on the upper side of the track and is a mirror-image of guardhouses of the same type. It was built according to the first known variant, namely of brick and stone. Both rooms are vaulted. The roof had been changed over time, but with the renovation in 2006, its original shape was restored.

In 1901, this guardhouse was abandoned due to its discomfort and small size, and a new one, significantly larger and more comfortable, was built in the immediate vicinity. The new guardhouse was given the number 666, and the old one was numbered 666a. Since then, the small guardhouse has had the role of an auxiliary facility. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the guardhouse got another number – 411. After the Second World War, most of the guardhouses on the Southern Railway were abandoned or thoroughly remodelled and expanded. Most of the abandoned guardhouses have collapsed long ago; therefore, it is almost impossible to find one. The guardhouse No. 666 is one of the few, if not the only such a guardhouse in our country, which has remained almost unchanged until now, in all its architectural appearance. (Tadej Brate)

In the autumn of 2006, at the initiative of Mr Bogomir Troha, Zgodovinsko društvo Borovnica (Borovnica Historical Society) started renovating the guardhouse building. The renovation was taken over by the local company Anto Milardović, s. p., and a lot of work was carried out by members of the Society. A large amount of funds was provided by the Municipality of Borovnica, and some funds came from other donors. The renovated guardhouse was opened at the 150th anniversary of the Southern Railway, in July 2007.

Signalling and communication devices were developing simultaneously with the railway infrastructure. In 1939, an article in Jutro newspaper briefly described how the signalling was carried out during the first years of traffic in the Vienna–Trieste line: “When I visited Ljubljana for the first time, a single telegraph wire was laid along the main road from Vienna to Trieste. It was laid in Nunska ulica. Later on, there were already two wires, and three lines in 1857. This year, the wires were laid along the railway line, and only one wire was left along the main road to Idrija. Guards used to live along the railroad so close to each other that they were able to see each other. Instead of a telegram, each guard had five round, large, red-painted baskets on high poles. When the Ljubljana–Trieste train arrived, each guard pulled up two baskets. For the train from Trieste, three baskets had to be pulled up. There were no other signals. Guards kept giving signals from one guardhouse to another until the report reached a certain place. At night, they had lamps for signals instead of baskets. And in the fog, every guard blew a horn. When an engine driver did not see whether they received the signs, they quickly stopped and went to the guardhouse to see, whether the guard might have fallen asleep forever. This has happened several times. No wonder. A railway guard had to work continuously for two days and two nights, and only on the third day they got a replacement for one day and one night …”

Baskets were replaced by modern signals, and horn-blowing by telephones. Today, the Ljubljana–Trieste line is and automated line, supported by a modern computer infrastructure. In modern trains, passengers can use the internet.

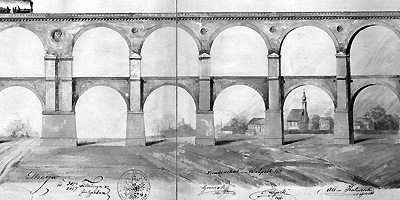

The Viaduct Construction

The Borovnica Viaduct used to be the largest bridging structure in the Southern Railway route between Vienna and Trieste…

The life of Viaduct

The railway line over the Borovnica and other viaducts was insulated with compacted clay…

The Second World War

On Easter Thursday, 10 April 1941, at five o’clock p.m., the Borovnica Viaduct was blasted under the command of Captain Žužek…

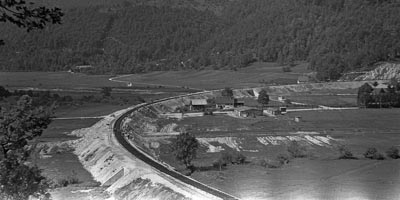

The construction of a new line

Borovnica was liberated on 6 May 1945, when it was entered by units of the 29th Herzegovina’s Strike Division…

This website is a part of the project »Thematic Park and Memorial Path of Borovnica Viaduct«, co-financed by the European Fund

for Regional Development (EFRD) throught the Local Action Group Barje z zaledjem.